zi2zi: Master Chinese Calligraphy with Conditional Adversarial Networks

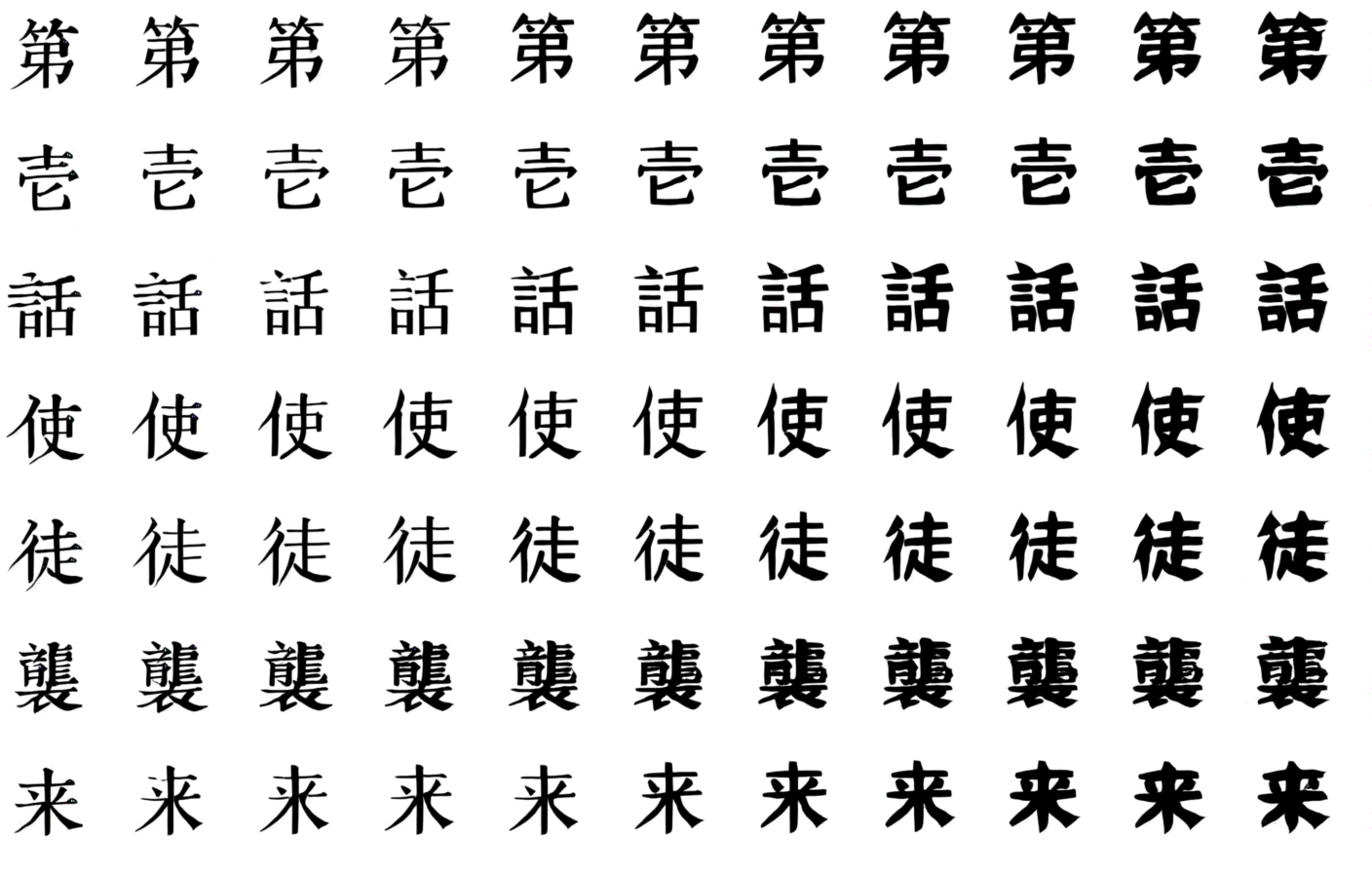

Generated samples. Related code can be found here

Motivation

zi2zi is the follow-up work for my last project, once again tackling the same problem of style transfer between Chinese fonts.

It is a pleasant surprise that the Rewrite project gets a fair amount of attention and interests, however, looking back, the result feels underwhelming. As an experimental attempt it does fulfill its purpose, but some big issues remain:

- The generated images are oftentimes blurry

- Fails under more stylized fonts

- Limited to learn and output only one target font style at a time

That is how zi2zi comes into being, an attempt to solve the above problems in one blow, this time blessed with the mighty power of GAN. On a more personal note, it also serves as a playground for me to tap into the wonderland of GAN and its variants.

One GAN to Rule Them All

TL;DR: It is a conditional generative adversarial network, combined from 3 awesome papers, with a little additional spice:

- Image-to-Image Translation with Conditional Adversarial Networks

- Conditional Image Synthesis With Auxiliary Classifier GANs

- Unsupervised Cross-Domain Image Generation

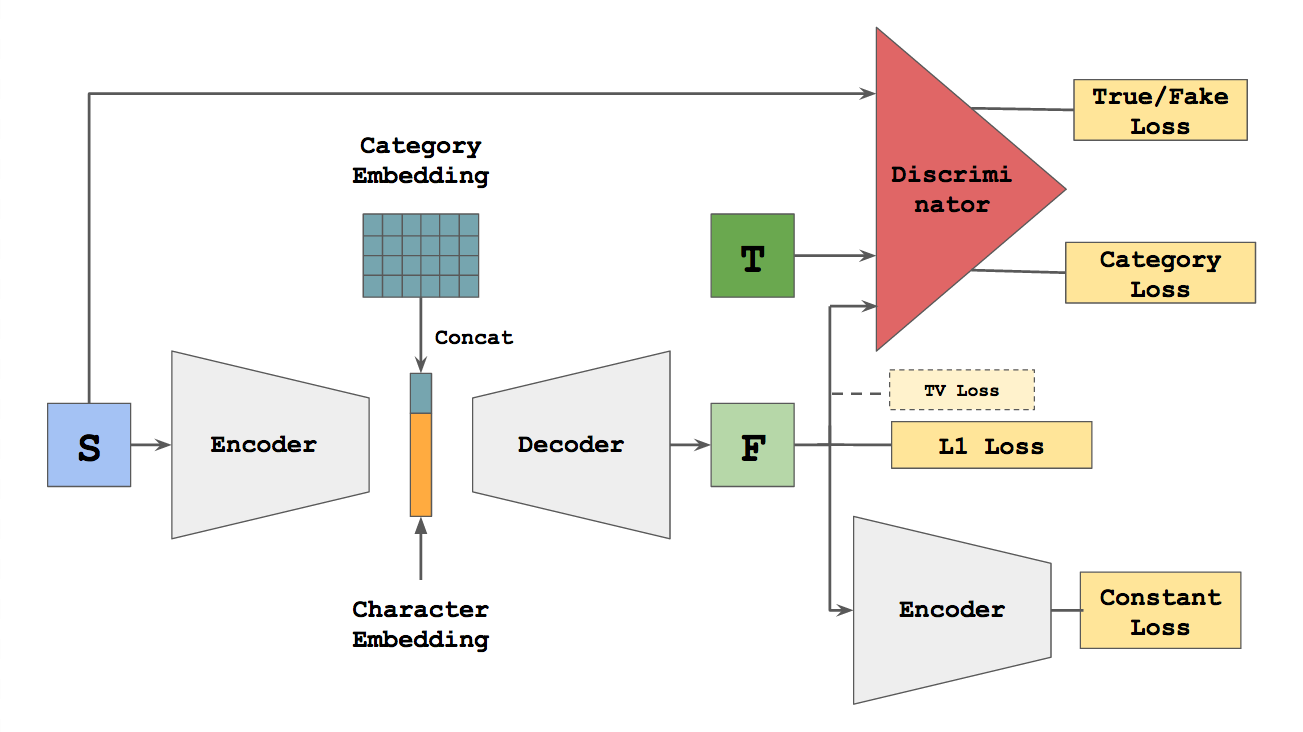

As its name hints, the zi2zi model is directly derived and extended from the popular pix2pix model. The network structure is illustrated below.

The structure of Encoder, Decoder and Discriminator are directly borrowed from the pix2pix, specifically the Unet model, which are detailed in the original paper’s Appendix section

Intuition

Imagine a human designer work on a new typeface, they are definitely not learning the alphabet from scratch! Real world designers go through years of training to understand the structure of the letters/characters and the fundamental principles, before they could design a font on their own. To reflect this, it is important to make the model not only aware of its own style, but other fonts’ styles as well. Thus it is essential to enable to model to learn multiple font styles at the same time.

Modeling multiple styles concurrently has two major benefits:

- The encoder gets exposed to many more characters, not only limited to one target font, but from all the fonts combined.

- The decoder could also learn different ways of writing the same radicals from other fonts.

By training multiple fonts together, it enforces the model to learn from each one of them then use the learned experience to improve the rest of the crowd.

Category Embedding for One-to-Many Modeling

Now we have a problem that same character could appear in multiple fonts. Vanilla pix2pix model doesn’t handle such one-to-many relationship out-of-box. Inspired by Google’s zero-shot GNMT paper, the introduction of category embedding solves this by concatenating a non-trainable gaussian noise as style embedding to the character embedding, right before it goes through decoder. By doing this, encoder still maps same character into the same vector, the decoder, on the other hand, will take both the character and style embeddings to generate the target character.

Losses, Lots of Losses

With category embedding, we now have a GAN that can handle multiple styles at the same time. However, a new problem emerges: the model starts to confuse and mix the styles together, generating characters that don’t look like any of the provided targets. Stolen from the AC-GAN model, the multi-class category loss is added to supervise the discriminator to penalize such scenarios, by predicting the style of the generated characters, thus preserving the style itself.

Another important piece of the model is the constant loss borrowed from DTN network. It follows a simple idea: the source and generated character should resemble the same character, thus they must appear close to each other in the embedded space as well. The introduction of this loss GREATLY, GREATLY improves the convergence speed, by enforcing the encoder to preserve the identity of generated character, narrowing down the possible search space.

Finally total variation loss is included, but from an empirical point of view, it doesn’t do much visible to improve the quality of generated images. Also for a lot of brush writing fonts, tv loss actually works against our real interests, so here it is left as optional.

How to Train Your (dra)GAN

GAN is truly a beast to deal with. Only recommendation is to watch the losses goes up and down, then praise the SUN!

Two-Step Training

One strategy I adopt is to split training into a two-step processes. First, train a big model with many fonts, then freeze the encoder. After that, we can choose to fine-tune the interesting individual fonts. This way, we have an encoder that trained to the extract abstract character structural information with tens of thousands characters, and a dedicated decoder to flesh out the target. This can be also viewed as a way of transfer learning using weight sharing.

Experiment Details

The big model is trained with 27 different fonts, approximately half Chinese half Japanese. For each font, between 1000 and 2000 characters are randomly sampled. During the fine-tune process, however, a different and bigger set of characters may be used, mostly in between 2000 to 3000 characters, with one exception that is trained with 4000 characters. And as with the same as Rewrite, the source font is SIMSUM.

It takes about 2 days on a single 1080 GTX to train the big model over 30 epochs, which contains about 29,000 examples. Learning rate is initially set to 0.001 with a batch size 16, with other parameters left as defaults (L1_penalty=100, Lconst_penalty=15). The learning rate is slashed by half after every 10 epochs.

The fine-tune process, however, varies case by case, depending on difficulty and performance, usually with possibly higher L1 and const losses, e.g you can try L1_penalty=500, Lconst_penalty=1000.

Notes

One seemingly trivial but fairly important thing to do before training, is to verify your data, for things like whether certain characters go missing, or whether the overall shape stay consistent between source and target fonts, since certain font might choose older or rarer ways of writing of some characters. Failure to do so would confuse the model and lead to mode collapse.

Have Fun With the Model

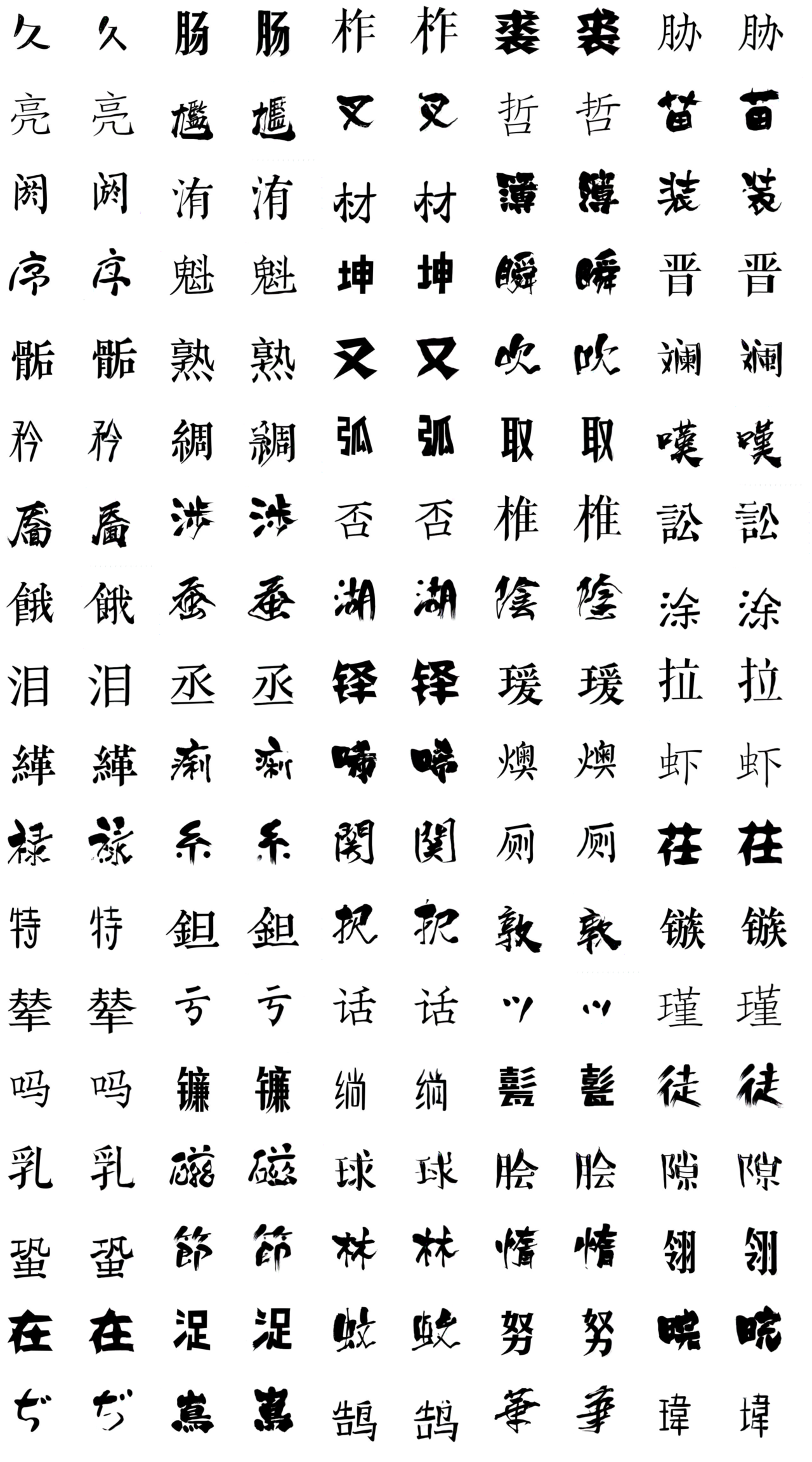

Compare with Ground Truth

The comparison with ground truth is shown below, with left being the original character and right as the inferred character:

The result is pretty exciting. Compare with Rewrite, for many characters, the inferred shape is almost identical to its ground truth. Another pretty noticeable improvement is, the zi2zi model can handle much more stylized and complex font than Rewrite, having not shown bias towards certain families of fonts.

Discover the Embedded Space

One perk we get from having continuous embeddings is that we can interpolate between different styles, and witness the states in between:

Below is the animation of transition between multiple pairs of fonts, which demonstrate the interpolation process in a more dynamic context:

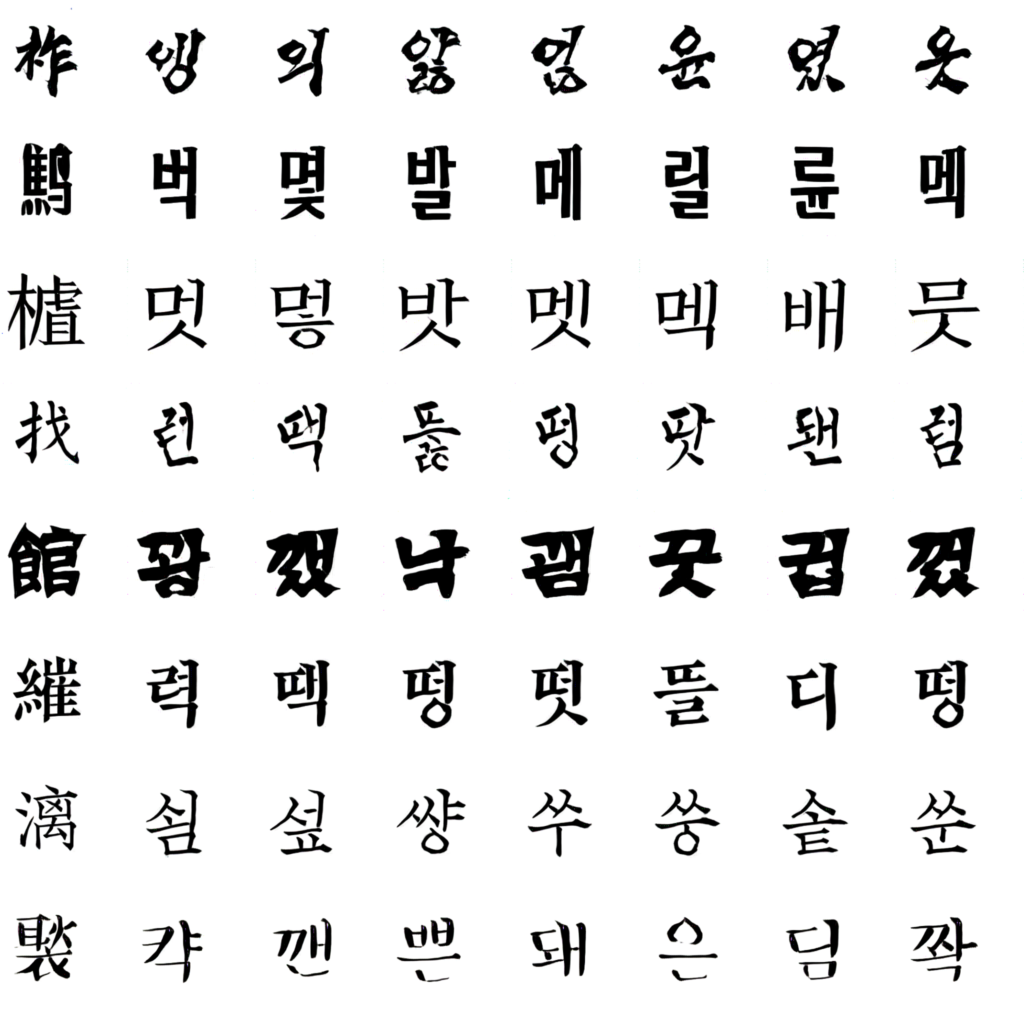

From 漢字(HanZi) to 한글(Hangul)

Chinese characters, no matter simplified or traditional or Japanese Kanji, are all constructed under common principles and a shared set of radicals. Would it be possible that this model just remember the radical shape and recombine them, and fails to generalize beyond that?

This makes Hangul(한글, 諺文), the Korean Alphabet, the perfect target for this question. Hangul, though having similar box-like structure as Chinese characters, is essentially its own system, with radicals that cannot be found in Chinese characters. It is an interesting challenge to test the model’s generalization capability beyond realm of Chinese characters:

The leftmost column is a sample of source Chinese font, with the rest being the inferred Hangul counterparts. Noteworthily, at this moment, the model has not see any Hangul characters during the training. As the result shows, the output seems to resemble closely the style of the source Chinese font, which is a fairly strong evidence that the model generalizes beyond simply remembering the radicals and rehashing them. It can infer the look of unseen radicals as well, indicating the capturing of deeper structural and style information.

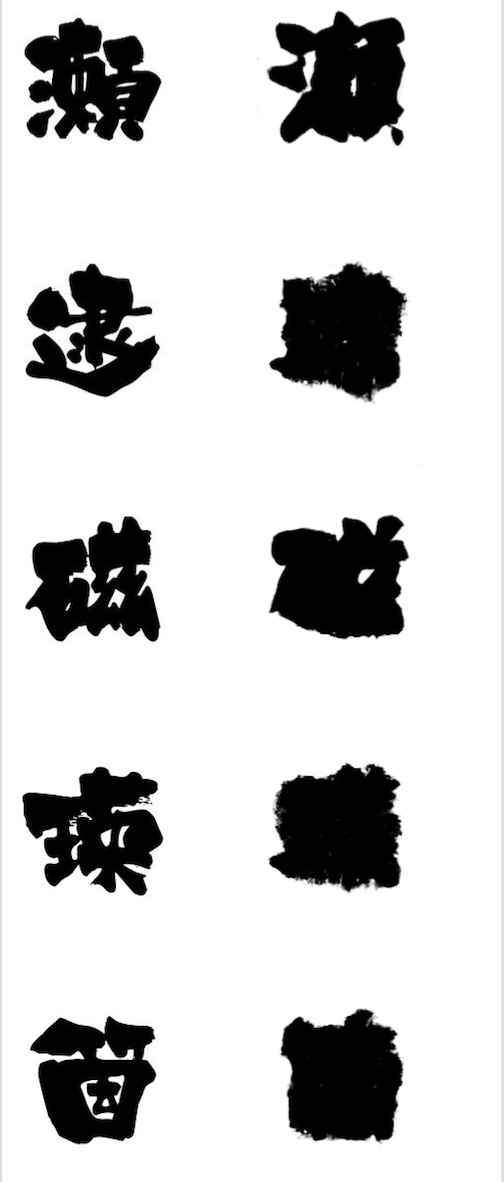

Failure Cases

The failure cases usually happen when the target font differs dramstically from other fonts it is trained with:

Such cases could be bypassed by fine-tuning the font in question, with a higher learning rate.

Tried but Didn’t Work

During the project, one thing I tried but didn’t work is using instance normalization instead of batch normalization. Specifically the Conditional Instance Normalization introduced in this paper. Though more parameters are used to represent each style, in reality it leads to longer convergence time, and higher chance of mode collapse. While still in the code, it is not used in any of the examples above. This may add as another interesting testament of the unreasonable representational power of BN.

Moving On

It is both surprising and exciting to see that GAN works so well with fonts. Even better, unlike existing approaches, zi2zi works in an End-2-End fashion, assuming no stroke label or any other auxiliary information which is hard to obtain, only the images of the characters. Even though for now, zi2zi works mainly for CJK family fonts, because of its E2E nature, it could easily extend beyond that. In my wildest dream, could we train a model to learn the typefaces of all the languages in the world, that later on, people just need to design a single font, then automatically get the corresponding fonts in all the other languages? That is indeed a very exciting future to witness.

Further on, it will be interesting to see how new GAN techniques apply to this problem. It is hard to believe, only in 6 months, new ideas are already piling up. Trying stuff like StackGAN, better GAN models like WGAN and LSGAN(Loss Sensitive GAN), and other domain transfer network like DiscoGAN with it, could be enormously fun.

Acknowledgements

Code derived and rehashed from: